A Look Inside Distant Worlds 2: Developing with the Stride Engine

Distant Worlds 2, the sequel to the acclaimed 4X strategy game Distant Worlds: Universe, was developed by Code Force and published by Slitherine. In this blog post, the developers answer key questions from the Stride community, offering insights into their experience using the Stride engine to bring their ambitious galaxy-spanning strategy game to life.

Table of Contents:

Intro 🔗

Our Stride community has been eager to learn more about the development of Distant Worlds 2. We reached out to the developers at Code Force to hear about their experience using the Stride engine to create this ambitious 4X strategy game.

We're incredibly grateful to the team for their generosity with both time and expertise. The depth and breadth of information they've shared, spanning everything from engine selection to performance optimization is impressive. Their willingness to provide such comprehensive insights is truly appreciated by the Stride community.

Some questions were answered by the team collectively, while others were addressed individually by team members: Elliot, the Lead Developer; Kevin, the Lead Artist; and Alex, the 3D Artist.

Buckle up and enjoy the ride, you're about to dive into a rich technical deep-dive and maybe learn something new along the way!

Engine and General Development 🔗

Why did you choose Xenko/Stride over other alternatives for Distant Worlds 2? 🔗

Our requirements for the DW2 game engine were:

- Full support for all features of C#/.NET

- High quality rendering, also allowing for the use of custom shaders

- Good asset pipeline support

Stride handles all of these areas very well.

One of Stride’s major strengths is how it integrates with .NET: it is nearly completely written in C# itself, and it stays up-to-date with .NET version releases.

You are not locked into any specific approach to writing code. You have full access to all parts of the .NET environment. You don’t have to use scripting tied to a specific custom version of .NET.

Instead you can simply make your own implementation of the Game class, overriding the Update and Draw methods from the base class. That’s the basic approach we took with DW2. We use Stride in two main ways for DW2:

- Rendering engine, using PBR models and materials with the scene/entity system

- Content/Asset bundling, using the Stride Game Studio to package assets for loading into the game

Beyond that we write all of our code as a standard .NET application with classes, structs, etc. We don’t use any scripts.

Additionally, because Stride is open-source, if you find an issue you can always fix it yourself. You can also figure out how things work by examining the source itself. Then, if required, modify things to work the way you want.

Stride also has great rendering with PBR materials. And it has a very nice shader model that allows you to write your own custom shaders.

How much modification was needed to adapt the engine for your needs? How difficult was this process for the developers involved? 🔗

We started experimenting with Stride back when it was called Paradox, around version 1.2. So there wasn’t much documentation back then. We had to just figure things out by examining the source. Documentation improved as the engine progressed through the 1.x versions, and became Xenko.

A key requirement for DW2 was to mix entity-level rendering for units (ships and bases) with custom shaders for the larger galactic environment.

Most of the DW2 environment uses custom procedural shaders to render things like planet surfaces, stars, nebulae and other items (see this article for details).

However for the unit-level rendering we wanted to use Stride’s PBR materials and the scene/entity system. The artists would build space ship models and materials which we would load into a scene.

We achieved this by separating out the custom shader rendering into pre- and post-scene rendering in the Game.Draw cycle. So we built our own rendering classes that inherited from SceneRendererBase and inserted them into the GraphicsCompositor.

This also allowed us to have rendering layers that excluded the post-processing effects (bloom, lens flare, etc). This was especially useful for the user interface.

There may be a better way to do all of this in Stride now, but that’s what worked for us.

We noticed references to both Xenko and Stride in the build. Are there specific reasons older files were retained during the transition? 🔗

Any remaining Xenko files are just a holdover from our development history. We should probably remove them 🙂.

How frequently do you update the engine for your project? 🔗

Initially we had some small custom changes to better support our pre- and post-scene rendering mentioned above.

When we went more heavily multi-threaded we made some updates in some areas of Stride to better handle this.

And whenever we want to move forward in .NET versions we have updated Stride to whatever version we were moving into (5, 6, 7, 8).

And as Stride itself progressed we have periodically pulled in some of those changes.

Stride’s approach to .NET has been a big plus. It’s quite amazing that we could move Stride to a new version of .NET ourselves.

Did you create issues on the Stride GitHub repository? 🔗

We have not done that. Much of our changes are very specific to Distant Worlds.

What were some notable technical hurdles in using Stride, and how did you overcome them? 🔗

Early on, the lack of documentation made progress slower. But this has improved a lot over time.

We worked quite a bit on getting Stride to handle heavily multi-threaded scenarios. We had to make some areas more robust and defensive, particularly around null-checking and iteration of lists.

User Interface 🔗

Which library did you use for UI elements in Distant Worlds 2? 🔗

What led you to choose the current UI solution over others? 🔗

Were there any features you found lacking in Stride for UI, and how did you address these gaps? 🔗

We initially tried out the built-in user interface elements of Xenko. But for various reasons we decided to instead build our own user interface system.

So for UI rendering we took the SpriteBatch class and built some basic controls: buttons, panels, textboxes, etc.

The input side is just reading keypresses and mouse actions from the InputManager class.

From there we added more functionality as we needed it.

Near the start of development it’s often hard to know exactly what you’ll need in the user interface. You have to tweak and extend things as you go. So it is important to have deep control over all parts of the user interface. For us that meant writing our own UI system.

I think this happens quite frequently in games, because they often have very unique and specific UI requirements. So it’s important to have full control over how the UI works, which might mean writing it yourself.

For DW2 we also had a requirement that the user interface be completely scalable. This was a major weakness of DW1, where the UI was fixed-size. So in DW1, as screen resolution increased, all the text became smaller and harder to read.

With DW2, building our own UI system allowed us to bake scaling into everything. So you can change UI scale in DW2 from the game settings and everything just automatically resizes and repositions, regardless of resolution.

How is the research screen (e.g., item order, dependencies) created? Are these elements procedurally generated, or are they manually crafted? 🔗

How did you create the research graph, including arrows and other visual elements?

The Research screen is custom-rendered. Most of the data in DW2 is heavily moddable, and the tech trees are a big part of this. So the rendering for research projects has to be data-driven.

We use some SpriteBatch helper classes to draw the lines and arrows between projects. The projects themselves use some basic textures for the main body.

Artists and Asset Creation 🔗

How did the artists find the asset creation process when working with Stride? 🔗

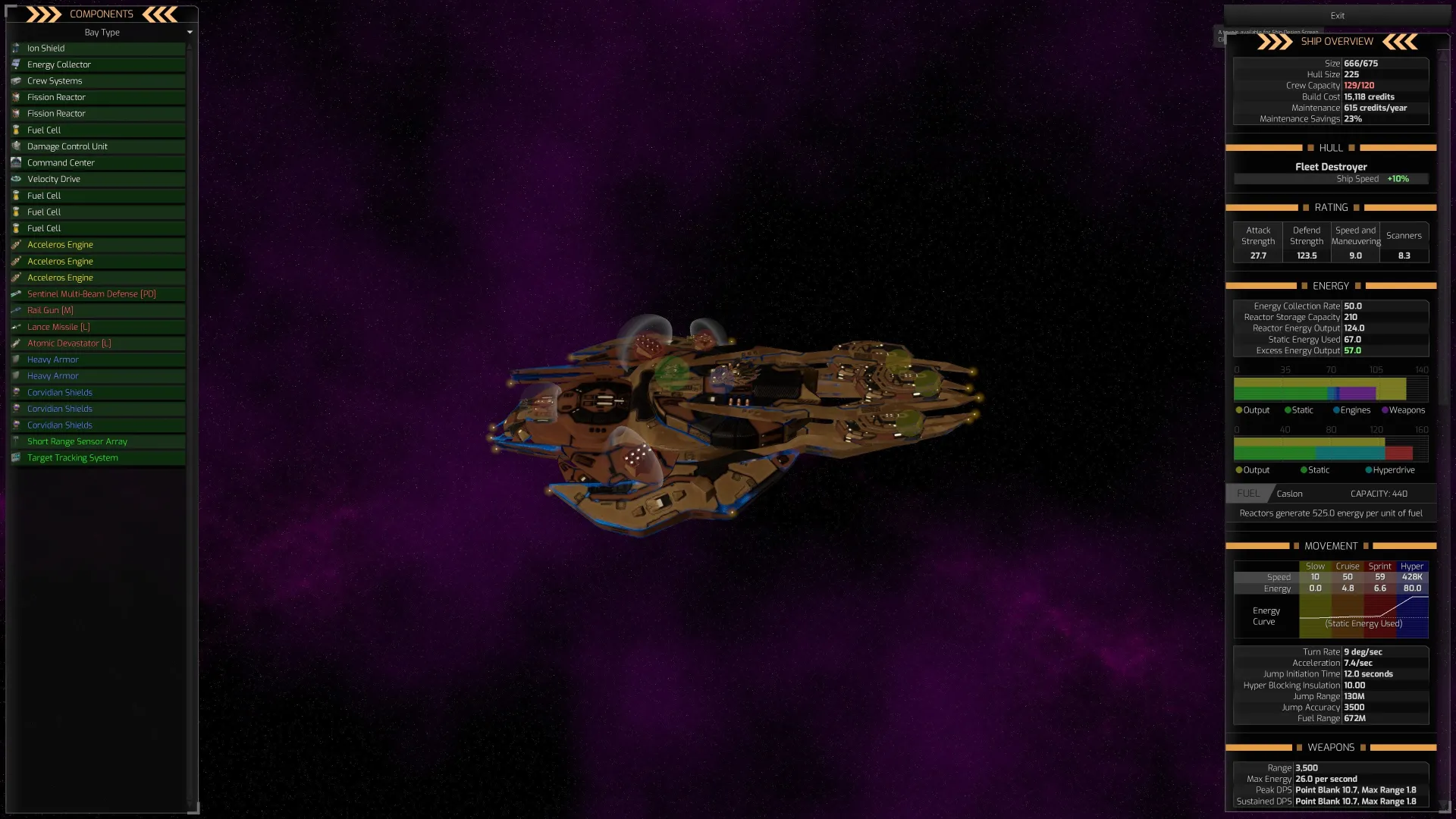

Elliot: DW2 uses lots of ship and base models with all of their associated textures. We utilize all the standard material features like Diffuse maps, Normal maps, Metalness maps, Emissive maps, Ambient Occlusion and Gloss maps.

So the artists use Stride Game Studio to simply bundle all the assets together before handing them over to the development side to use in-game.

Kevin: It works well and is easy and intuitive. I like that there's multiple ways to do the same thing (i.e. clicking and dragging or using the 'click to add' interface for assigned textures for instance)

Alex: The workflow is a lot like Unity or Unreal. It’s pretty simple for making PBR 3D models. The material creation is flexible and easy to pick up if you know Unity. It feels smooth and straightforward overall. I found it quick to get started with and the tools don’t get in your way.

What are their thoughts on the physically-based rendering (PBR) pipeline in Stride? 🔗

Elliot: It’s very nice and produces great looking scenes. It’s pretty easy to understand.

Kevin: Works great and again is easy to use. The only issue is there is a marked difference between my editing software (Substance Painter), Stride's asset preview, and in game. Though at least those last 2 items aren't the engine's fault.

Alex: I’d say the artists thought it was pretty good. It works well and everything looks just fine in the game. There’s not much to add really. No problems to complain about that we know of. It just does the job nicely!

Did you encounter any challenges or limitations with shaders, and how did you address them? 🔗

Elliot: Initially we had to figure out how we were going to mix our custom procedural environment shaders with the Stride PBR material rendering. But once we had settled on our approach to this, most things were pretty smooth.

Early on, it took a bit of digging into the Stride code to figure out what we needed to do with PipelineStates, EffectInstances and other items. We ended up much as described in the Stride documentation here: Low-level API.

Kevin: Plenty. Some of it was learning a new engine and some of it was a lack of certain features. A huge bonus for artists would be to be able to have a node-based editor for shader effects. Right now (at least on our current version) things like animated UVs has to be done manually.

Alex: When it comes to challenges or limitations with shaders in Stride, I’d say we didn’t run into much. The default shaders were solid and covered all our project needs so far. We haven’t tried adding custom ones yet though. I did give it a shot once using an example shader but it didn’t go well. The editor crashed and I was left scratching my head. I might revisit it later and hope for better luck. From that one try, it felt like adding a custom shader would take way more effort than you’d expect. Maybe I missed something simple but I wish it was less frustrating to bring a custom one into the project.

Level Design and Prefabs 🔗

How was the level creation process using Stride for your team? 🔗

DW2 doesn’t use levels in the normal sense. The galaxy is an open-world and is entirely procedurally generated. So we manage view changes and the transition between locations and scenes in code, adding and removing items as needed.

Was the Prefab system easy to use for level designers, and did it meet your expectations? 🔗

We use Stride Prefabs mainly for particle effects. We instantiate particle effect Prefabs for various in-game effects, like weapons fire, hyperdrive effects, explosions, etc.

These work well, allowing our effects artist to create things as he likes them, then package them together as a Prefab in Game Studio.

In code we can then use these effects pretty easily, supplying their in-game world transform to scale and position them where they need to be.

Did the component system in Stride prove to be intuitive for designers? 🔗

DW2 is probably not a typical game, so we only use the scene/entity system inside the game code itself, dynamically creating and updating scenes as needed.

Stride Game Studio is really just an asset bundling tool for us.

DLC and Content Expansion 🔗

Could you briefly outline the steps involved in creating a DLC for Distant Worlds 2? 🔗

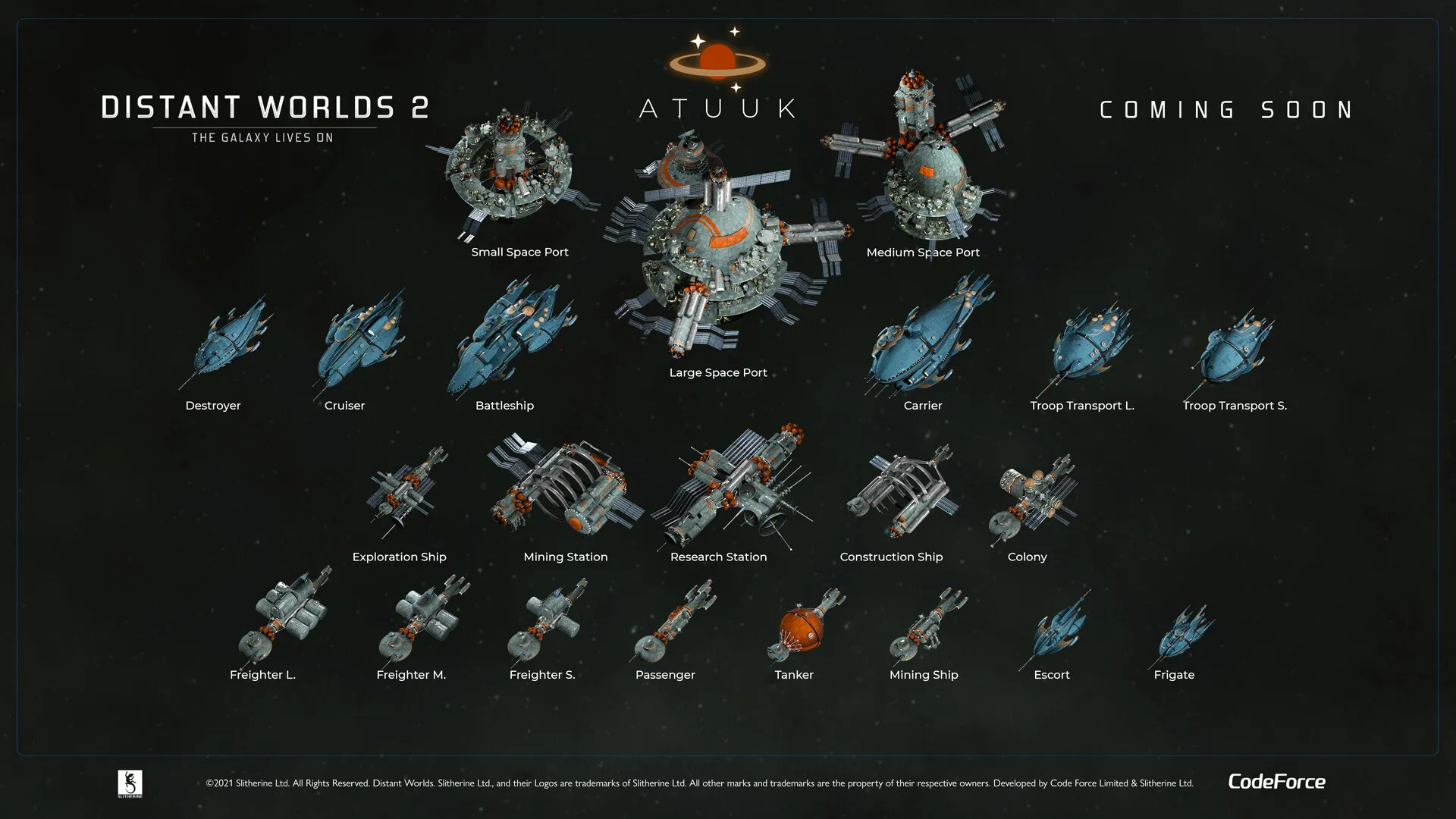

DW2 DLCs typically involve adding one or more new alien factions into the game.

Each faction has new game features unique to them. They likely also have their own unique government type, which also has new features. So there is a lot of code to support this.

From the art side each new faction involves around 25-30 new ship and base models, each with their own full set of materials and textures.

Ship models in DW2 are quite detailed, with individual meshes for various parts of the ship, e.g. engines, weapon mounts, hangar bays, sensor dishes, etc.

So the models are created as super-sets with all of the meshes that might be used. Then the player can design their own ships using the in-game ship editor. As they add or remove components to the ship, the game enables or disables appropriate meshes.

These models and textures are packaged together into faction-specific Stride bundle files inside Game Studio. We then load these bundles in-game for the new factions and can then show their ships and bases in scenes.

Additionally we also have animated characters for each new faction. These are implemented as 2D texture atlases that are animated using Spine. In-game we can play appropriate mood-based animations for the characters.

How do you detect whether a DLC is installed or not for a player? 🔗

Each distribution platform has their own mechanism for this. So whether it’s Steam, GOG or something else, we use their inbuilt features to check this. Then we can load the appropriate bundle files with all of the models and textures for that DLC.

Performance and Optimization 🔗

Source: Steam - Distant Worlds 2 - Screenshots by Shrikebe

Source: Steam - Distant Worlds 2 - Screenshots by Shrikebe

The game achieves impressive performance, especially during large-scale fleet battles. How did you manage to optimize for several simultaneous battles, each with many ships and fighters? 🔗

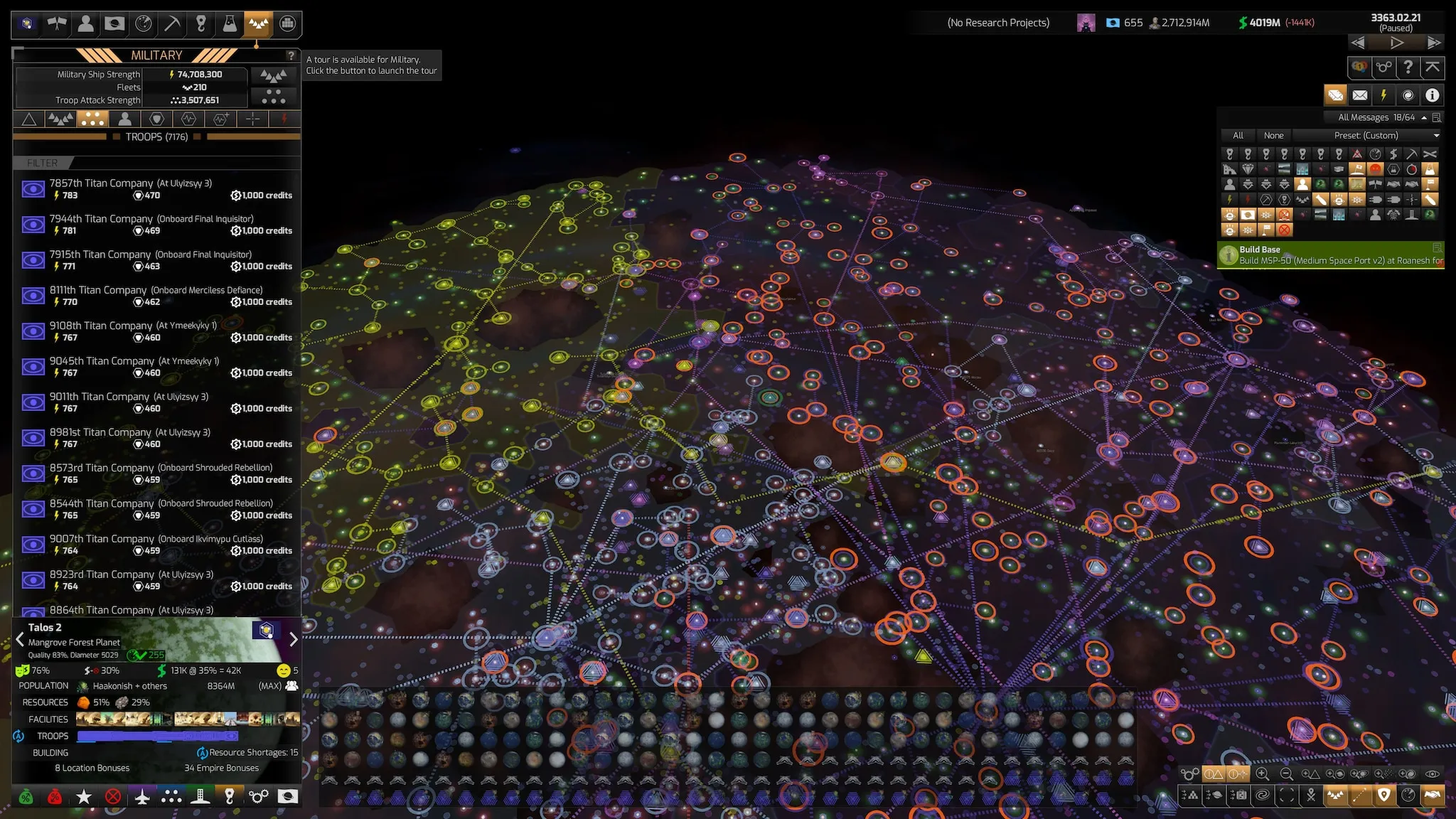

Performance optimization has been an ongoing consideration throughout development. As we add new game features we periodically need to profile and improve performance in slow areas.

Large galaxies can have a huge number of individual units and factions, all of which can have extensive logic that needs processing at some minimum level of frequency. We have test games that have more than 250,000 ships, fighters and bases. Individual locations/scenes might have over 3000 units in a single battle.

Most of DWs performance demands are on the logic side, i.e. we are CPU-bound. So there have been 3 basic approaches we have used to improve logic performance:

- Improve specific algorithms, i.e. find faster ways of calculating something

- Cache the outputs of expensive operations as much as possible and only update them periodically

- Use multi-threading to parallelize processing across all CPU cores. This requires very good locking, especially when iterating lists. It also requires a lot of defensive coding to check for null references which would never occur in single-threaded situations.

Rendering in DW2 does not generally encounter performance issues in the same way as the game logic does. However there are some optimizations:

- In large scenes we may exclude drawing for small meshes in models as the view zooms out, thus reducing the total number of draw calls

- We use instancing in a number of areas to handle elements with a high draw count, for example the stars in the galaxy view are drawn using instancing

Are there any specific techniques or approaches you'd recommend for simulating large-scale scenarios like fleet battles? 🔗

Early on we made the decision to optimize the way weapons are rendered to minimize draw calls. So all weapon blasts in a scene are drawn in a single draw call using a custom shader that handles all of the different textures and animations for all the various weapon types.

The rendering is wrapped into a single vertex buffer with camera-facing billboards for each weapon blast. The shader determines what to draw using a number of texture arrays that allow various rendering features, e.g. flipbook animations, scrolling beams, etc.

This places some definite constraints on what we can render. We can’t just go crazy with expensive particle effects. But it has huge benefits for performance.

Weapon trails are handled in a similar way, where a single vertex buffer contains all of the trail particles, and is rendered with a single draw call per frame.

AI and Game Systems 🔗

Source: Steam - Distant Worlds 2 - Screenshots by VoiD

Source: Steam - Distant Worlds 2 - Screenshots by VoiD

Did you require any kind of editor extensions? How did you implement them? 🔗

Our use of the Stride Game Studio is really just as a tool to bundle assets into the game. So we didn’t need this.

Which serialization method did you use for saving games? Was it a database, YAML, or a mix? 🔗

The static source data for the game entities is mostly just XML files. Things like planet and star definitions, ship components, alien races, government types, research projects, etc.

We have some internal tools for editing these files. And we also have auto-generated schema for most of these data types.

For saving and loading games we use low-level binary serialization. So .NET BinaryReader and BinaryWriter with streams. This requires hand-coding all of the serialization, but has big payoffs in performance.

This also allows easier version management as you add new data to the game. You can have conditional loading of new values based on game version.

What AI libraries did you use? What techniques were used for AI, such as for fleet formations, battle decisions, or engage/retreat behaviors? How was diplomacy handled? 🔗

All game logic is custom written for each system. We don’t have any 3rd-party AI libraries.

Logic happens at 3 main levels:

- galaxy-wide logic that affects everyone

- faction-wide logic where each faction makes high-level plans to explore, expand and conquer

- unit-level logic where each ship decides what mission to select to advance their factions goals

We try to make each entity have sufficient logic to carry out it’s normal tasks and to also be able to respond to unexpected events in a reasonably intelligent manner. So the units can be given missions from a faction-level AI or manually by the player, but they can also assign themselves missions that make sense for the current situation.

This kind of logic forms the bulk of the code in the game. So this logic really IS Distant Worlds.

In addition we have an extensive advisor system that can provide suggestions on what to do next. These advisors are deeply integrated with the faction- and unit-level logic. When you switch an area of the game to ‘advisor-mode’ then you will get periodic suggestions in that area that you can either approve or reject.

So for Colonization you will get suggestions about which planets to colonize. Approving the advisor suggestion will build a new colony ship and send it off to claim the new planet as a colony for your faction.

If you instead had the Colonization area fully-automated (no advisor suggestions) then the game logic would simply carry out whatever it thought was best, automatically establishing new colonies.

You can fine-tune how each area of game logic works, even when it is fully-automated. These policy settings tweak precisely how the automated decisions are made, allowing you better control over things. This ‘intelligent automation’ is a key feature of Distant Worlds that allows it to scale very large while still being manageable for the player.

The game logic (including the advisors) is constantly being developed and improved. With the very open game style of Distant Worlds, there are endless unexpected situations that can prove challenging for the game logic to handle. So we are always extending the game logic to handle new things.

Future Use and Recommendations 🔗

What types of projects do you think the Stride engine is perfectly suited for? 🔗

For us, the key strength of Stride is it’s deep integration with the .NET ecosystem, providing easy access to all of its tools and features. This has meant that we can build a standard .NET executable that simply uses Stride for rendering. That flexibility is great.

Are you planning to use Stride in the future, beyond maintaining Distant Worlds 2? 🔗

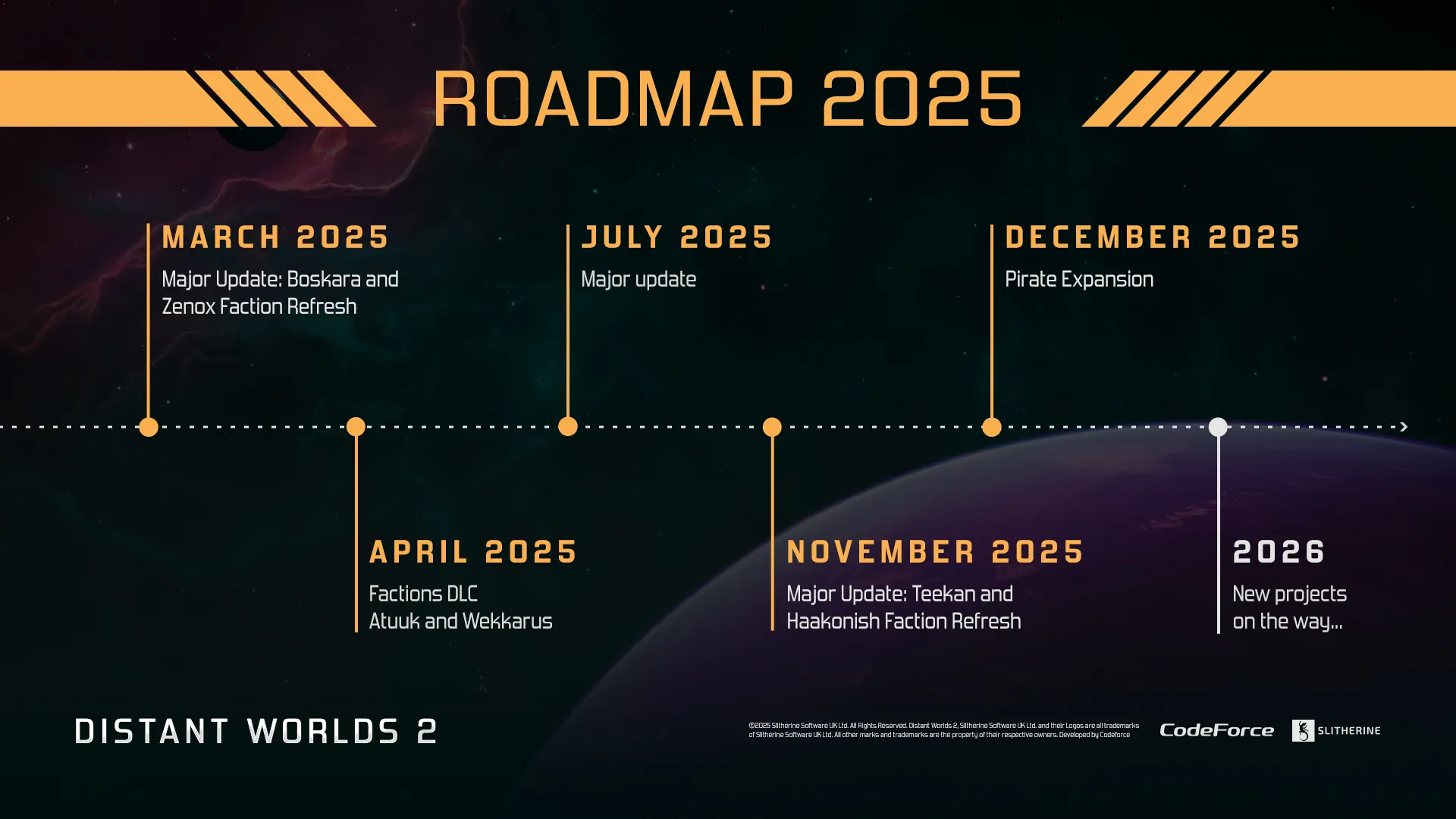

We currently have a development roadmap laid out for the next 12-18 months, with no end in sight after that. So Distant Worlds 2 will be keeping us busy for the foreseeable future 🙂. Stride will continue to be a core part of that work.

How can the Stride engine be improved to help the modding community? 🔗

Each game no doubt has its own unique requirements. But Distant Worlds modders mostly encounter Stride when packaging up assets to use in the game. This typically means creating a new Stride project that just contains static art assets (textures, models, etc). The goal is to generate a Stride bundle file that can then be loaded in the game.

So any improvements to bundle creation and updating are always welcome.

One small pain-point that still exists is renaming the bundle files.

In Stride Game Studio, the normal build process generates the bundle with the name “default.bundle”. This is ok if you put all of your assets in a single project. But when your game gets bigger, that is not viable.

In Distant Worlds we load many different bundles. The models for each faction are contained in their own bundle. We currently have 14 factions, so that means 14 different bundles. We also have other bundles for other parts of the game. Each of these bundles must have different names.

There is currently no way to change the bundle name directly from within Game Studio (that I know of). Instead you have to hand-edit the YAML in the *.sdpkg files, changing the bundle name and adding the appropriate Selectors.

That may sound fairly simple, but it can still be an extra hurdle for modders. Having bundle-renaming built into the Game Studio would make this much easier.

Conclusion 🔗

The journey through Distant Worlds 2's development offers valuable insights into what's possible with the Stride engine. Code Force's experience demonstrates how Stride's deep integration with .NET creates a flexible foundation for ambitious projects, allowing developers to focus on crafting unique gameplay experiences rather than wrestling with engine limitations.

What stands out most is how the team leveraged Stride's strengths—particularly its rendering capabilities and open-source nature—while developing custom solutions where needed. Their approach to performance optimization, particularly for large-scale battles involving thousands of units, provides practical lessons for developers working on similarly complex simulations.

We'd like to extend our sincere thanks to the Code Force team for sharing their expertise and experiences so candidly. Their willingness to detail both successes and challenges offers invaluable knowledge to the Stride community and game developers at large.

For those inspired by what you've seen here, we encourage you to explore Stride for your own projects. Whether you're developing strategy games like Distant Worlds 2 or something entirely different, Stride's combination of powerful rendering, C# integration, and flexible architecture provides a solid foundation for bringing your vision to life.

If you're already using Stride for your projects, we'd love to hear about your experiences in our GitHub discussion or on our Discord server. Your stories and insights help strengthen our growing community of developers.

Links 🔗

- Steam: Distant Worlds 2 on Steam

- DW2 Forum: Matrix Games Forum

- YouTube: Slitherine Games on YouTube

- GitHub Stride DW2 Discussion: GitHub Discussions

- Kevin: You can find him on our Stride Discord server as @KevinC

GameStrategy4X

Any comments? You can start 🗨 at GitHub Discussions or Discord.

Edit this page on .